Electro-Euroatavism: Genre & playlist (go-genre)

A video version of this article, with audio examples, is available on YouTube.

For decades, I have been interested in music that blends ancient European musical traditions—folk and medieval—with a dark, driving, electronic sound. Unfortunately, the way musical genres work, today, is entirely incompatible with this eclectic combination. That’s why I’ve created a new genre, which I call “electro-Euroatavism,” that encompasses these characteristics.

I chose this genre-blending phrase based on the concept of an atavism, which a noun that means going back to ancestral roots.

In this article, I’ll introduce this genre, define its characteristics, and let you listen to some examples of this genre’s musical artists. I’ll also define what “medieval” music actually is and explain its continuity with the present.

There are a lot of stereotypes about medieval music. But, let me start with an allusion to the past:

Dost thou delight in the music of the Middle Ages, which is wondrous fair and sweet, like unto a maiden of noble birth, fair and pure, dwelling in a castle yonder?

Did this sentence perhaps capture the essence of medieval music for you? Does it make you think of long abandoned musical traditions that are not part of a living tradition, today? Do you think of simple, plain music devoid of improvisation, melodic character, and richness? If so, you might be surprised to learn that these are all inaccurate stereotypes.

Let's start with the quote, above, which was my misguided attempt to communicate using "medieval" words and phrasing. While what I wrote is assuredly how people spoke in the past, it's actually modern English, spoken during the Renaissance, after the Middle Ages ended. How would this phrase actually have been spoken in the year 1000, during the proper Middle Ages, prior to English being heavily infused with French words?

Licað þe þæt sangcrafte þæs middelaldres, þæt is wundorlic, fæger, and swete, swylce mæden of æðelan cynne, fæger and clæne, wuniende on castele geond?

The sentence, above, is essentially a foreign language to today's English speakers, but it is English —or, rather, a very old, archaic version of it. Just like this Old English sentence might surprise you with its authenticity, so might the reality of music during the the Middle Ages, which lasted approximately from the year 500 to the year 1400.

What we know about music during the Middle Ages and how it differs from modern music

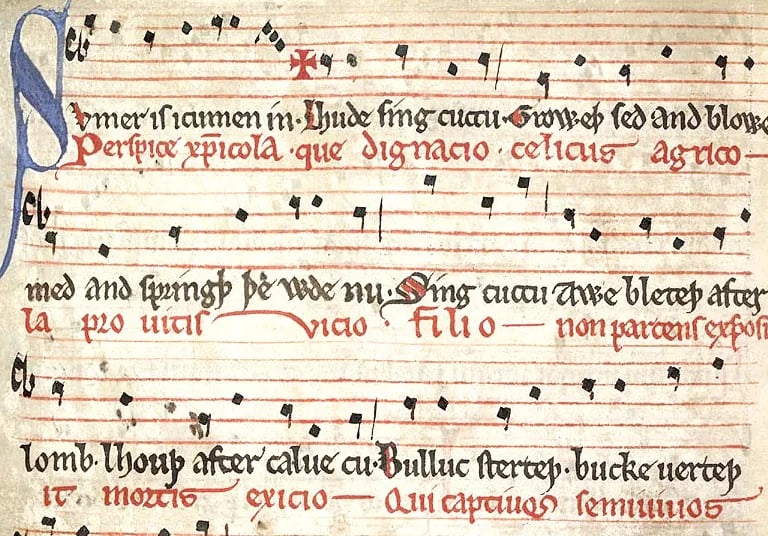

The reality is that we don’t know a whole lot about music during the Middle Ages, especially before the year 1000. The reason is fairly simple: Hardly anything was written down. And, even if accurate musical notation was available, the full scope of a medieval performance will always be unknown because of the central role of improvisation. Thus, even assuming we have accurate scores for medieval music—which we do not— relying on musical notation, alone, inevitably paints an incomplete and inaccurate picture of the music of the Middle Ages. But, that does not mean extant written musical notation isn't valuable—it is—but this record is, unfortunately, rather thin.

The modern concept of sheet music, where specific pitches and duration of notes, a key signature, measures, and words in context with a melody did not come together until the Baroque era (about 1600). Before then, some degree of interpretation, increasing greatly as one went further into the past, is required due to the lack of complete musical notation — for instance, note duration was not recorded until the thirteenth century and measures weren’t recorded until about 1500. The result is that, especially prior to 1000, there is often more guessing than facts. For this reason, some scholars emphasize that it is important to refer to the ancient Greek treatises upon which medieval musicians relied to supplement incomplete notation. With this broader knowledge, it then becomes possible to develop a theory for how medieval music was performed, especially in relationship to improvisation.

As Farya Faraji, an expert in traditional European and Middle Eastern music, explains, supplementing extant musical notation with these ancient treatises strongly suggests that ornaments (improvised notes that are often not diatonic, or part of a 7-note scale) and melismatic singing (singing a syllable using several often ornamented notes) were highly likely to have been a normal part of medieval music. Or, in a simpler sense, medieval music might have sounded like what we conceptualize, today, as traditional Middle Eastern music or some forms of modal European folk music. (I will explain the concept of "modal" music, below.) This claim makes more sense given that medieval European and Middle Eastern music share a common ancestor in ancient Greek music. The characteristics of traditional European folk music, which evolved from medieval music (as opposed to being heavily influenced by classical music theory), add additional evidence for the ornamented richness of medieval music.

Thus, the supposedly simple sounds of medieval music, confined to only a diatonic scale, very much appear to be a stereotype. Why is this the case? Faraji explains how musicians, well within the modern era, only used extant (and incomplete) medieval sheet music to recreate performances. Because their perspective was not informed by ancient Greek musical practice, such as improvisation and tuning methods that were well known to medieval musicians, modern musicians had little choice but to rely on classical music theory to guide their recreations. So, while not strictly inaccurate, a better word to describe this situation is impoverished. Thus, these performances of re-created medieval music are essentially sterile, devoid of the improvised, ornamented richness and authentic tuning methods that would have originally been present. Had these later musicians paid a bit more attention to contemporary modal European folk music, however, they might have realized that elements of medieval music were still alive that could have informed their approach.

To be sure, actually listening to today's modal European folk music to provide evidence for how medieval music was played is critical. While we do know that secular music surely existed prior to 1000, there is no written evidence for it — the only extant records we have for music in this early era is entirely based on religious music sung in Christian churches. By the year 1300, however, some of the first secular/folk songs began to be written down. But, even in this latter era, there are only a handful of secular songs that have any kind of recorded musical notation. And, just like the religious music of the Middle Ages, the notation is often quite thin.

Even though our written information is scant, it paints a broad, evolutionary picture of Western music development through the Middle Ages. Prior to 1000, it appears that music, sung in churches, was mostly a cappella (without instruments). The early church frowned on instrumental music, but into the middle and late periods of the medieval era, instruments were increasingly used in religious contexts. Even so, throughout the Middle Ages, in religious music, instruments (e.g., pipe organs) were typically not accompanied by singing, but rather the performance was alternatim — first the instrument, which stops, and then singing, but never both, together. Thus, polyphony (the possibility of more than one musical note sounding at a time) was limited in the early medieval era, although some forms of polyphony did exist in vocal music. By the end of the Middle Ages, however, polyphonic instrumental and vocal compositions were being written down, so it can be assumed that their performance was common.

There is also evidence for polyphony, in the form of instruments accompanying singing, with early secular or folk music, but again, essentially nothing was recorded prior to 1300 of this nature, leaving us to speculate about what came before. The troubadours and minnesingers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries had a profound influence on the development of secular music, but it’s unclear how this might have impacted formal, religious music, including the development of musical polyphony. The written record, however, points to Gregorian chants, and the introduction of the organum — a second voice, sung, at the same time with another voice — around the year 900 as the start of polyphony; by the twelfth century, especially centered in Paris, polyphony in music became quite sophisticated, but still lacked important characteristics for tonal music, namely a specific key center and the regular use of major and minor chords in a structure emphasizing harmony. The Renaissance (after 1400) marked the turning point in Western music where keys and harmony began to play central roles, becoming fully developed by the Baroque era. In sum, medieval music simply didn’t feature keys, chords, or harmony. To be sure, much of the so-called contemporary “medieval” music heard today is, in reality, often neo-Renaissance music because of its embrace of harmony and lack of modal features.

Because harmony is not the goal of medieval music, pre-Renaissance polyphony is quite different from the kind of polyphony that defines music today. Since the Baroque era, the concept of the major or minor key — a specific sequence of eight played notes that define an octave, different in where the half steps are placed — and harmony has dominated musical compositions. Modern music is fundamentally about harmony driven by chord progressions — three or more notes played at once that typically consist of at least an interval of a major or a minor third followed by a fifth. Thus, music, in the modern era, is conceptually about “stacking” notes to create chords. Medieval music — when more than one note is played at once — doesn’t work this way.

When more than one note sounds at the same time in medieval music, it is often, in a sense, accidental. Rather than music intentionally composed as stacked notes played at once — vertically — medieval music is best conceptualized as a horizontal affair where different melodies are played at the same time and their notes just happen to sound simultaneously, hopefully creating a pleasing sound. When these notes are playing together, the intent was not to create a chord, but rather to, in general, avoid overall discordance.

But, as with much of medieval music, relying on surviving written scores, alone, to define "desirable" intervals paints an incomplete picture. Many of the medieval musicians who formally documented their music—including their strong preference for consonant intervals—also wrote about how ancient Greek treatises influenced their performance, which indirectly indicates that their music was intended to be ornamented when it was performed. Because of non-written ornaments, likely added through improvisation, these "undesirable" intervals, outside of the diatonic, surely existed in medieval music as it was performed, including augmented intervals and quarter tones. It is important to note, however, that ornaments were not intended to be the dominant feature of the music. In this sense, the written sheet music of the medieval era was only intended to capture the most important ideas of a musical piece; thus, performers had a great deal of latitude in its performance.

Because of the high probability that medieval music included ornamented improvisation, some degree of transient discordance was unavoidable and thus, acceptable. In other words, the expectation that, for instance, a Gregorian chant would never have included a diminished fifth (a very discordant interval) seems to be inaccurate. On the other hand, it would be fair to assume that a musical piece would not have been built around the foundation of a diminished fifth. What makes this transient discordance different from what is found in classical music theory is that it wasn't introduced to add tension that would then be resolved with a consonant interval; rather, ornaments existed to add color to the composition.

Again, what is assured in medieval music is that the overall nature of the prominent intervals, over an extended period of time in the piece, were likely to be consistently consonant. Although the written evidence isn't abundant, based on scores that have survived, there seems to have been a strong preference for consonant musical intervals, in this order: the octave, the fifth, and the fourth. While sometimes intervals of a third did occur, their presence is not so common in the written record, and seconds even less. Minor seconds and diminished fifths were reportedly abhorrent — in fact they were commonly associated with demonic influences, based on contemporary authors of the day.

This sonorous quality in the recorded scores of medieval music is easy to hear through motions like parallel fifths, which might be strange sounding to the modern ear, but were frequent in polyphonic medieval music. (Classical music theory seeks to avoid parallel fifths, whenever possible, conceptualizing the sound as “weak.”) The medieval emphasis on the dominant notes in a music piece being consistently consonant is different than what is found in classical music theory. Again, in classical music theory, there is a kind of dance between discordant and consonant intervals, with discordance driving toward consonance so as to seek resolution.

Tuning was also different in the Middle Ages because equal temperament — dividing an octave into 12 equally divided notes — did not exist, only becoming widely used in the Baroque and Classical eras. Two tuning systems, dating to the Greeks, were widely used, instead: Pythagorean and just intonation, both typically dividing the octave into twelve notes and then using eight of them which highly prioritized a pure fifth and fourth, along with other pure intervals, but other numbers of notes per octave were also used, unlike in most modern music. When performed, however, chromatic or quarter tone ornaments would likely have been introduced, but again, these would not be the dominant notes in the music.

Critically, medieval composers did not create their work in what we know today as a “key,” but, rather, used what is known as a “mode.” A key helps to create a tonal center, which is a single note that a melody or chord progression moves toward. Keys help to establish harmonic structures based on chord progressions — minor or major — that support this tonal center. Keys are consistent in being either minor (with two different flavors) or major. A mode, on the other hand, is not intended to support harmony or chords, but rather to create tonal colors between various intervals in a melody. As opposed to a key, the places in which there is a half-step (i.e., the smallest interval that is normally playable) can vary greatly. Medieval music used many different modes, such as Ionian (equivalent to a major scale), Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian (equivalent to a minor scale), and Locrian. With the tuning systems in use, which were not based on equal temperament, there was no possibility of modulating into a different mode (akin to modulating into a different key) because the intervals are not evenly divided across the octave; in simple terms, such an operation would sound horribly discordant and, as such, is not found in medieval music. A piece of music is consistently in one mode for its duration.

In terms of rhythm and song structure, medieval music — when we have some idea of a time signature, which is not always the case — used many time signatures, from today’s common 4/4 to more uncommon signatures (at least compared to pop music), such as 6/8 or 7/8. While the notes may be indicated in extant documentation, the way that they are grouped to create a rhythmic structure is often unknown; how percussion was used in medieval music can therefore be a bit of a challenge to decipher. And, because of the lack of documentation of measures, many times we can only guess how the repetitive units of medieval music manifested, whether they were in groups of 4, 3, 16, 20, or some other number.

Lastly, we know a bit more about the particular instruments that musicians used in the Middle Ages — especially the middle to late periods. These include stringed instruments like the dulcimer, fiddle, harp, lute, lyre, and organistrum (like a modern-day hurdy-gurdy); wind instruments like bagpipes, clarion, flute, horn, and pipe organ; and percussion such as bells, clappers, cymbals, frame drum, Jew’s harp, and pandeiro. Many of these instruments are readily recognizable as progenitor’s of today’s Classical instruments; some have survived in a form that has changed little, over time. Of note is that some of these instruments — much like modern-day bagpipes — played two notes at once: a drone (a bass note that did not change) and a melody. This drone works particularly well with modal music.

Getting in the mode: Defining medieval musical authenticity through modality

Given the preceding context, how much of so-called “medieval” music made today is reasonably authentic? In other words, if you were to play this music to people who lived 800 or 1,000 years ago, would it sound remotely like something that would have been familiar to them? The answer is complicated, but there are some rather clear cases where calling such music “medieval” might be a bit of a stretch. Of all the elements that we know define bona fide medieval music, I would argue that people from this long ago era would clearly recognize modality, as opposed to harmony, in compositions. Modality also happens to be the most widely documented aspect of medieval music.

Perhaps the most egregious use of medieval branding is in the bardcore genre, which reimagines popular songs in a supposedly medieval style. By definition, works in this genre fundamentally rely on harmony and chord progressions, violating a core tenet of medieval musical authenticity based on modality. While the instruments (or the sounds of instruments) might be reasonably authentic, one could make an argument that this, alone, is insufficient.

To be sure, as this example shows, the bogeyman of medieval music recreation is harmony, which is fundamentally ingrained in Western culture and in the composers who grew up in this culture. It can be difficult for composers to escape its clutches, which makes the novel creation of truly modal medieval music somewhat rare, especially when there are multiple instruments and/or vocals in the composition. Part of this is that modal songs can sound strange or “off,” begging for a missing third or to have some form of dissonance resolve through a chord. Thus, musical artists often find themselves having to work against their cultural instincts when creating neo-medieval music: it’s not so easy to set ingrained cultural responses aside.

Thus, I would argue that the most important aspect of creating music that has some semblance of medieval authenticity is to assure a composition includes modal elements to a relative degree. We do know, with certainty, that medieval music (up until the very end of the Middle Ages) was quite assuredly modal. Other aspects, however, such as how percussion was used, time signatures, and measures are often just an educated guess, at best.

While some musical purists disdain neo-medieval music that is not authentic to the highest degree possible, this perspective ignores the creative potential of bringing the past into the future. I do not advocate for this obsessive authenticity, which I think unnecessary for the overall enjoyment of music. While bardcore, in my mind, is rather a stretch to call “medieval,” I think it is fair to label many artists’ compositions as influenced by medieval traditions if they’re somewhere in the spectrum from including a minor amount of modal compositional elements toward basing their work fundamentally on a modal framework. But, in this definitional constitution, modality is more important than the sound of instruments — or any other musical aspects — in defining authenticity.

European folk music might be the most authentic medieval music

As I alluded to in the section above, modal European folk music might just be the most authentic representation of medieval music available at present.

While the religious music of the Middle Ages died and was resurrected much later by musicians who imposed a rigid, classical structure on it, secular medieval music continued, in a relatively uncorrupted form, to the present via modal, European folk music traditions. While contemporary European folk music incorporates classical musical elements to some degree, when a modal structure dominates, this music appears to—more than any other musical forms, today—accurately convey the authenticity of medieval music. That's why one can commonly find the consonant intervals of the octave, fifth, and fourth in many European modal folk traditions along with ornaments and melismatic singing, which are not "supposed" to be part of medieval music, but, in reality, probably were present 1,000 years ago.

What exactly, then, is modal European folk music?

As Europe is a rather large geographical area, there are many examples of modal folk music, including from the following geographical regions:

Southeast Europe/The Balkans (e.g., Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Macedonia, Greece) in which Phrygian, Mixolydian, and Aeolian modes are common, such as the music of Valya Balkanska, Kočani Orkestar, Ensemble Pirin, Vaska Ilieva, Melina Merkouri, and Svetlana Spajić.

Central Europe, such as the Carpathian region of Ukraine where there is a variant of the Dorian scale with raised 4th and 6th, and lowered 7th degrees such as the music of Folk Ensemble Hutsul.

Northern Europe, such as Celtic folk music from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Brittany that focus on the Mixolydian mode such as the music of Altan, Lúnasa, and Boys of the Lough.

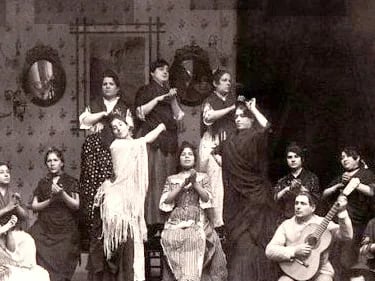

The Iberian Peninsula, where Arabic, microtonal maqamat modes are common along with Phrygian, Mixolydian, and Dorian modes, such as the music of La Bazanca, Asociación Etnográfica Bajo Duero, Ringorrango, and Grupo Folclórico de Pinheiros, Quempallou, and Lenda Ártabra.

Undoubtedly, there are many, many other general and specific examples that I have missed.

And, out of all of the European folk music traditions, I am most strongly attracted to the folk music from the Iberian Peninsula because of its complex rhythms, syncopation and time signatures expressed through a variety of percussion instruments, many of which have continued to be influenced by Middle Eastern traditions more so than other European folk traditions.

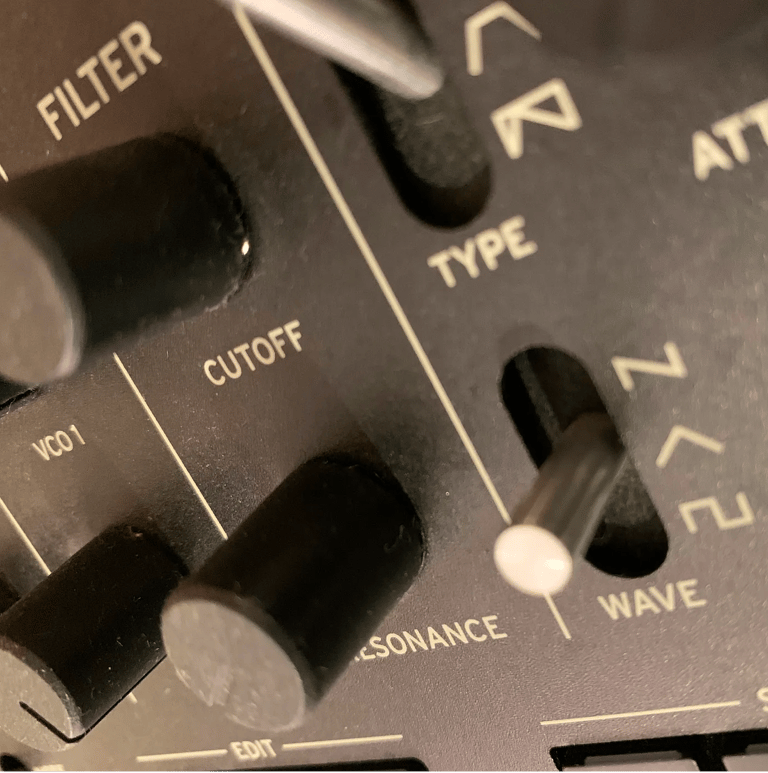

The surprising overlap between medieval and (some) electronic music

I admit that I am quite partial to electronic music, mostly because I’m emotionally moved by its sounds — especially the sounds of analog synthesis. As it turns out, music composers and theorists, during the Middle Ages, were also interested in the relationship between the quality of sound and its impact on the listener.

Many medieval philosophers wrote about the impact of the sounds, in music, on people. Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, writing in the sixth century, in his unfinished book, De Institutione Musica Libri Quinque, described the unique timbres of string, water, and percussion instruments and, through a reference to ancient Greek philosophers, their impact on people. Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas were deeply interested in the relationship between timbre, modes, and spiritual feelings, viewing music as a way for people to move closer to the divine and the beauty of God’s creation. To be sure, many other medieval philosophers, such as John Scotus Eriugen, Hugh of Saint Victor, and Martianus Capella, viewed the specific sounds in music as a gateway to spiritual growth. Specifically, Albertus Magnus, writing in the thirteenth century, believed the sounds in music could evoke joy, sorrow, anger, and peace and even heal the sick. Although these philosophers did not reduce their theories to specific instrumental timbres, their writings express an important relationship between the sounds in music and their effect on people.

From today’s perspective, many electronic music genres have elements similar to medieval music, especially in relation to modality. A particularly relevant example is electronic body music (EBM), which arose in the 1980s in Germany and Belgium, with heavy influences from industrial and punk while drawing from disco’s penchant for a steady beat. Like medieval music, EBM features many ostinatos and repetition. But, in particular, EBM music is often modal in its use of sustained drones and unconventional scales. Echoing the medieval organum structure, a typical EBM track will have, at most, two identifiable pitched elements: a prominent droning or modal bassline (Phrygian and Locrian variations are common) and a vocal. Much like later European folk music from the Balkans or Iberia that was influenced by European and Middle Eastern medieval traditions, the vocal typically will be in unison with the bassline or a minor or major second above or below it. What is usually absent is a semblance of harmony, chords, or chord progressions. Examples of these musical groups are Front 242, Nitzer Ebb, and Portion Control, but there are also newer artists, such as Spark. Over time, many artists that started in the EBM genre, such as VNV Nation and Apoptygma Berzerk, have rejected modal constructions and embraced harmony and chord progressions, becoming more synthpop in character, forging a new genre known as future pop.

A more recent genre, phonk, is known for its Phrygian modality and stabbing parallel fifth intervals; example artists include Witchz, Kiraw, and Kordhell. Like EBM, there is a distinct industrial sound to phonk. But, EBM and phonk, to most people, would be a stretch to call “medieval” primarily because these genres have an industrial sound that is antithetical to the “softer,” more melody-driven quality of music with bona fide roots in the Middle Ages.

There are other genres, however, with artists that are more overt in their medieval influences, not only in the modal and instrumental qualities, but their names and even lyrics, which can be in Latin. Some examples include dungeon synth — artists like Nox Arcana, Spellbound Mire, and Inlustris — which is often inspired by medieval-themed games. Darkwave is a genre that has a number of electronic, medieval-inspired artists, especially in the inaccurately named “neoclassical darkwave” genre; example artists include Love Is Colder Than Death, Snakeskin, and Vas.

Many of the artists who are driven toward a more authentic medieval sound in their electronic compositions are considered to be part of the Neue Deutsche Todeskunst (New German Art of Death) movement. Some of the artists in this genre, such as Qntal, Helium Vola, and Deine Lakaien have adopted the “electro-medieval” moniker. Although this is not a common genre name, it does more accurately reflect music that combines electronic and medieval influences than do other genre names. Qntal is commonly credited with creating the “electro-medieval” name and the spin-offs from this group — Helium Vola and Deine Laiken — have carried this branding, forward.

Threading the needle through medieval and electronic influences: An electro-Euroatavism playlist

Since mid-2024, I’ve been curating a Spotify playlist of songs from artists that represent the key themes I’ve discussed in this article, namely an emphasis on a modal construction, as opposed to a tonal one, that emphasizes harmony. My tastes lean toward other elements found in the European folk music derived from medieval traditions, so I also feature electronic folk artists that use alternate tuning systems. Lastly, I particularly like heavy synth basslines and intricate percussion with traditional instruments, like the folk music from Castile and León, Spain. Overall, the songs on this playlist are dark and driving with a sense of mystery, but they are also believably medieval in character. While I like artists from other genres who use modal constructions, such as phonk, their sound is overtly contemporary and not believably medieval; I would also not suggest that the artists from these other genres are intending to be identified with “medieval.”

In a sense, the best way I could describe this playlist is what rune/Viking/Nordic folk and Balkan and Iberian folk music would sound like with an electronic influence. In other words, the sound is like combining Danheim, Wardruna, and El Naan and infusing their sound with driving, dark electronic basslines and synthetic cinematic soundscapes while keeping their emotive vocals. Some of these preferences are derived from my own music project, Novit Terminus. As my ancestry is German and Spanish, there is a natural feeling in going back to my roots in my own creative work, which is also expressed in this playlist.

As of the writing of this article, these are the artists and groups on this playlist. Most of these artists are not well known (an average of about 15,000 listeners a month; many are much less), but deserve wider exposure:

One artist who should be on this list, but whose work is not currently on Spotify, is Femina Faber (you can listen to her music on YouTube and other online streaming services).

Where past meets future

Electro-Euroatavism is an enchanting intersection of ancient European musical traditions and modern electronic sounds. By exploring the modal nature of medieval music, its later folk developments, and its surprising parallels with certain electronic genres, there is a unique musical space where the past and the future converge. While the music of the Middle Ages remains enigmatic, the underlying principles of modality and the emotional impact of known music, from this era, provide a solid foundation from which contemporary artists, such as myself, draw inspiration.

As I continue to be influenced by this genre, I think it is important to acknowledge the delicate balance between authenticity and innovation. By respecting the historical context while pushing the boundaries of sound design, these artists consistently create magical, captivating, and evocative music.

For more on these topics, see:

Everist, M. (2011.) The Cambridge companion to medieval music. Cambridge University Press.

Faraji, F. (2022). "The Medieval European singing style and its correspondence with Middle-Eastern singing" via YouTube.

Faraji, F. (2023). "The common origins of European and Middle-Eastern music" via YouTube.

Van Deusen, N. (2011). The cultural context of medieval music. Praeger.

Van Elferen, I., Weinstock, J.A. (2016). Goth music: From sound to subculture. Routledge. Routledge. R